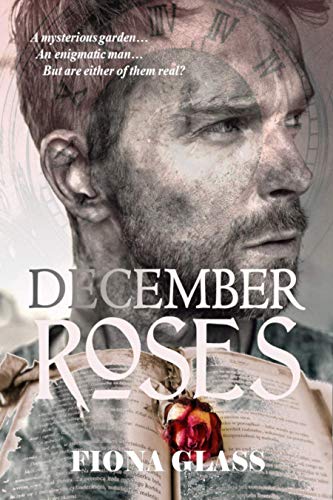

December Roses

December Roses LGBT Paranormal Romance/ Ghosts

Vitreous Press

December 1, 2020

200

Recovering from a bombing in 1990s Belfast, British soldier Nat Brook is sent to remote army rehab unit Frogmorton Towers to recuperate. At first he’s lonely and depressed, but then he finds the remnants of a once-beautiful garden, meets the enigmatic Richie, and begins to fall in love.

Gradually, though, he realises there’s something odd about Frogmorton. He can rarely find the same place twice, and Richie proves every bit as elusive as the Chinese pagoda or the Scottish glen. Nat begins to question his own sanity, because if the garden is imaginary, what does that make the man he loves?

Faced with the shocking truth, Nat must decide whether to stay with the army - even though that means hiding his sexuality - or find acceptance elsewhere.

This poignant ghost story was originally published as 'Roses in December' by Torquere Press but has now been extensively rewritten.

Reviewed by Ulysses Dietz

Member of The Paranormal Romance Guild Review Team

Moody and quietly magical, Fiona Glass’s “December Roses” is a contemporary book set in the fairly recent historical past (mid-1990s); but it feels like a story out of another time entirely. Of course, there are moments when it is.

Sergeant Nathaniel Brook (Nat to his friends) has been badly wounded in what he and the British army think is a deadly IRA bombing in Belfast in 1993. The prologue tells us what really happened, and that becomes the Chekov Gun lingering in the background throughout the book. Meanwhile, after months of healing in hospital, Nat is moved to an extended-stay rehab center housed in the rambling Victorian mansion of an estate called Frogmorton Towers. At Frogmorton, Nat is to receive ongoing physical therapy, but also psychological care for his PTSD.

Restless and not a little misanthropic from his bomb experience, Nat begins to seek refuge in the sprawling, unkempt gardens at Frogmorton. While the house itself has a strong presence in the narrative, it is the gardens that become so very important in Nat’s journey to self-rediscovery. This aspect of the book is richly rewarding, speaking as it does to the British love of gardens. Although American estates had some pretty fantastic gardens in the years between the Civil War and World War I, we as a nation have never loved our gardens quite as much as the British still do. The glory of a great garden, as well as its ephemeral fragility, becomes a crucial metaphor in Fiona Glass’s narrative.

The paranormal aspect of this book is subtly woven into the story, and evolves into a Twilight-Zone-esque mixture of romance and low-key horror. Throughout, the reader is probably one step ahead of Nat Brook, although that would depend on how clever a reader you are. I found myself lulled into a pleasant romantic haze until the penny dropped. Some people will figure it out far sooner than I (or the main character) did.

My only disappointment with this book was in the character of Nat Brook himself. Don’t get me wrong; he’s well developed by the author, who takes great care to explore Nat’s motivations and the workings of his mind. Nat, however, being a man just ten years my junior (reckoning by the chronology of the book’s setting), is a gay man who has chosen service in the military over any sort of happy personal life. This is because, just as was still true in the USA in the 1990s—lesbian and gay men were routinely drummed out of military service with dishonorable discharges (at least in the USA). Many chose to abandon military careers for fear of discovery, while others hid successfully, living secretive, emotionally stunted lives worthy of the 1950s or 60s. Nat himself is fully aware of his choices, and never questions their validity. My trouble is that he seems to be filled with a sort of passive self-loathing. He is lonely and isolated in the world, and he apparently feels that this is appropriate for someone like himself.

At a moment late in the book, Nat questions something significantly good that happens to him, “…because he wasn’t sure he deserved to be happy after everything he’d done.” Never once does Nat seem to question the moral validity of the military’s stance on homosexuality—even though I know that hundreds of LGB servicemen and women in the US routinely fought against such rules for decades until President Clinton’s “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” was repealed in 2011. Nat’s shrugging acceptance of his own unworthiness (shunned by his family, lacking in friendships) is sadly off-putting. The army’s attitudes and behavior are infuriating, but not to Nat. There is one effort in the book to point out the injustice of the army’s rules—by a closeted lesbian doctor—but it is weak tea indeed.

Thus, ironically, the poetic twist of the plot that ends the book—on a beautiful, romantic note—left me feeling let down as much as uplifted. I don’t at all mean to criticize Fiona Glass’s lovely storytelling and elegant handling of language. Most readers, I suspect, will feel otherwise, and take unalloyed pleasure in this lyrical narrative of love lost and found.